The Earth Below The Sky Above

How I Turned Layered Landscapes Into Photoweaves

People who see my Fabricated Land photoweaves in person often ask for the stories behind them, so over the next few weeks I will be discussing specific works from the series, getting under the hood of the theory, history and process behind the final weaves.

In Scotland, I find myself looking anew at familiar landscapes as I research their history. It becomes increasingly clear that the shorthand dichotomies associated with Scottish land – highland versus lowland, natural versus man-made, past versus present – are not necessarily in opposition but rather concurrent, woven together as distinct threads that are visible close up, like pixels on a screen, or tiles on a mosaic. Black remains black and yellow is still yellow, but together the diverse visions of landscape modify one another, their colours flicking back and forth like a Bridget Riley painting.

Fabric of Land

The modern nation of Scotland was built on wool and weaving. Tartan’s wild discord, I felt, was a perfect metaphor for the clashing ideas that have shaped Scottish identity.

I decided to begin experimenting with woven photographic prints. I also wanted to disrupt the photographic delusion that time and space (and land) are static. By cutting a still photographic print into strips and physically weaving it together with strips from another still, I could create a dynamic, near-abstract view of a landscape. My aim was to explore the ways in which a landscape can be fabricated – a glen can be shaped as much by stories as by a glacier. The weaves approximate the multiple perceptions that I experience in a landscape and are a metaphor for the competing processes that created it.

The Process

i. My photoweaving process begins with reading. Read books to read the land. This informs the locations or ideas I need to find in the images.

ii. Using a drone, I make aerial swatches of specific landscapes, looking down from directly overhead. This may involve multiple trips in various weather conditions or even across different seasons.

iii. Back in the studio I then choose shots that resonate or jar with each other. I think about how to reveal the differences between views but also the deeper similarities and how to harmonise polar opposites of colour or story into one weave.

You can watch the whole process here.

Polarising Vision

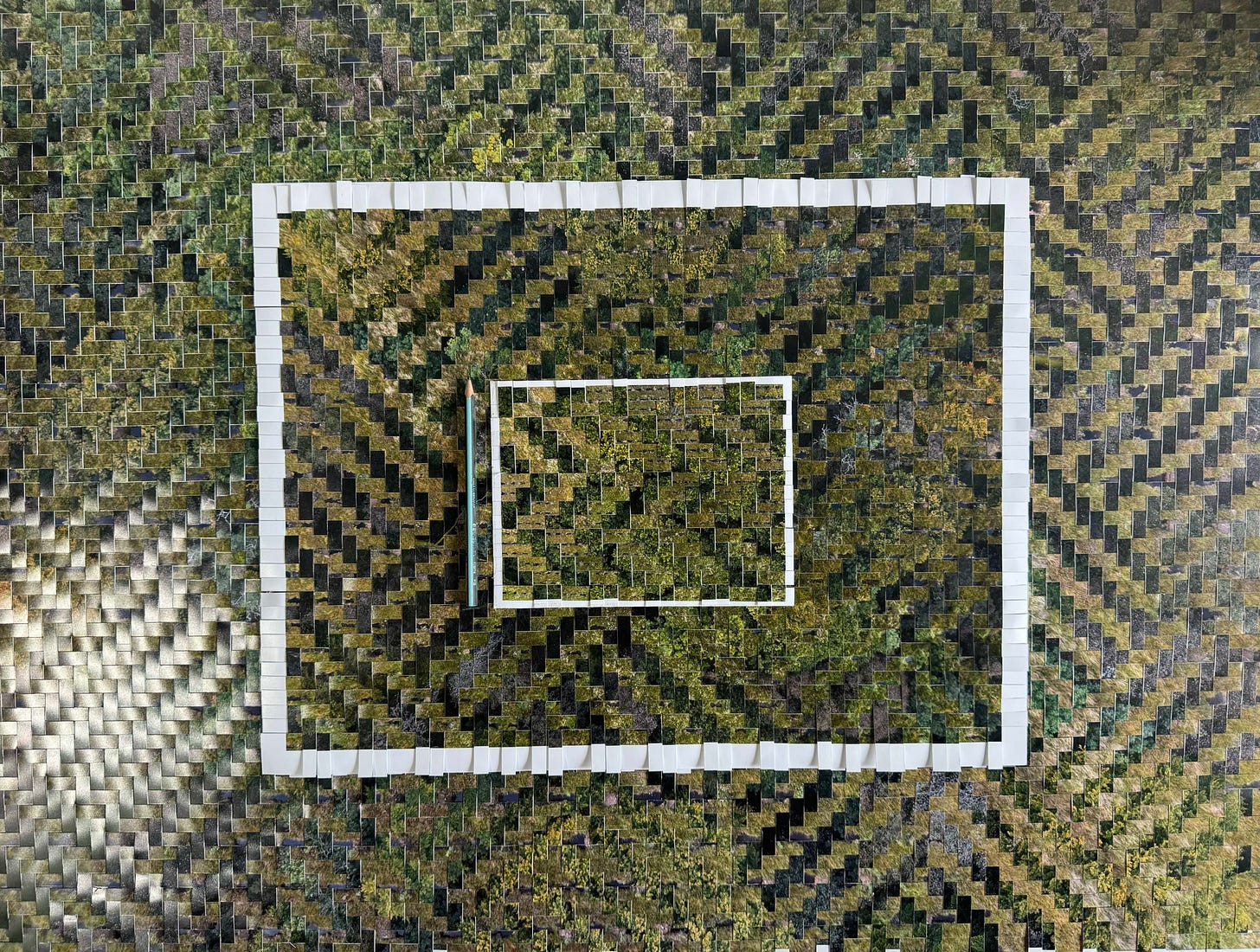

What these images represent might seem like polar opposites, but generally a little research reveals common ground. Above is a photograph I took of a grassy bogland, and below is a climax forest. The bogland is a rewilding site on the hill of Dumyat near Stirling, next to where I grew up, yet the straight lines across the land declare human presence. Indeed, the hill gets its name from the fort of the Pictish tribes who cut down the trees, transforming forests into bogland. And while the forest canopy is full and vibrant, its name speaks of lost industry – Mine Wood, where silver and even gold were once sourced for the Scottish royal crown. The beech trees that make up the forest originate from the south of England and were planted with gusto in the Victorian era. The landscapes appear superficially different, but both have been formed by human interaction and influence on ecosystems.

Studies

Having researched traditional Scottish tweed and tartan patterns, I try out different weaves to bring the stills together. I make multiple iterations of woven small prints to find what works best, then I scale up – first six times larger, then twenty times larger than the study weaves.

Synthesis

The result is a complex print that can appear simple when viewed from a distance but on closer inspection reveals intermeshed layers of narrative.

The above work (with me for scale) is currently on display at the University of Stirling, and, like other original works, is available for purchase. It is the first at this scale and one of three in a triptych I have planned. Two of the three are complete.

Film Stills: Duncan McGlynn