Art Changes The World

But the World of Art Remains the Same

This is a free to read article.

All new paid subscribers will receive weekly articles and now a 30 x 42cm poster print from my new series Gulls of Greatness, unveiled last week. No AI is used in the making of these articles. Click below to upgrade.

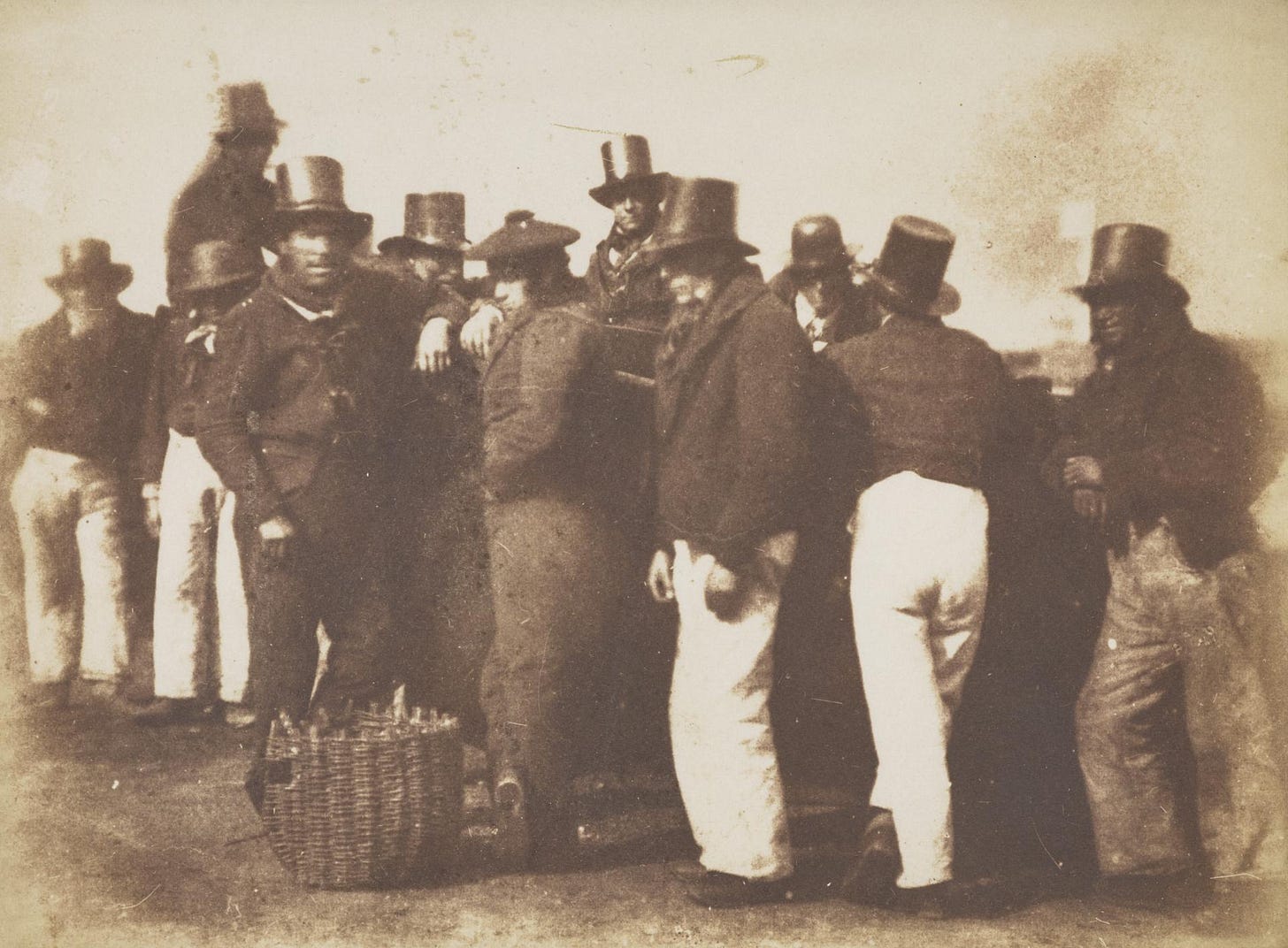

Earlier this year, I wrote about how, at the dawn of photography, two trailblazing Scots refined the new medium by documenting a protest by Protestants in the mid 19th century. Hill and Adamson may seem a world away from contemporary photography, but in the art world, some things never change, and I was reminded of this with the recent arrival of Steve McQueen’s Resistance show to Edinburgh. The show’s pieces date from 1903 onwards – sixty years after Hill and Adamson first collaborated – and chart photography’s continuous role in protest and change over the past century.

This week, I want to reflect on the parallels between Hill and Adamson’s lives and the business of making art today.

What Photo Pioneers Can Teach Us Today

The surprising collaboration between a chemist and a painter arose as Hill and Adamson experimented with cutting-edge technology, the calotype. If they were around today, they would likely be pushing the standard camera to its limits as well as testing out the latest digital sensors, flying cameras, AI tools or applying older processes to pressing contemporary issues.

They talked of books and projects they never finished.

Productivity came in seasons, literally. They struggled to work in winter owing to sickness and, more importantly, because the low light hindered their art. (Scottish winter was no joke in the time before the dry robe.)

Hill frequently wanted to give up. He wrote to friends doubting the process, then soon after gushed with passion for the medium.

They were artistically driven, but also business-minded, considering the outcomes and possible costings of their work.

They were constrained by health, legal and money issues.

Hill and Adamson used crowdfunding to preserve the 16th-century home of John Knox, which Edinburgh council was going to knock down (a classic Edinburgh council move). The building juts into the Royal Mile to this day. Bad for traffic, great for history, and supported by an artists’ print sale.

People didn’t reply to their correspondence. In particular, Henry Fox Talbot, who invented the calotype process, ignored their pleas (and those of their friends) for his permission for them to use the process outside of Scotland. Talbot came north, staying within metres of the Hill & Adamson studio at Rock House but didn’t even pop in for a cuppa.

They were opportunists, capitalising on the fact that patent laws didn’t extend to Scotland, meaning they could pioneer the art of the calotype, whereas others elsewhere could not.

They focused on their immediate surroundings, revealing a depth and insight that comes with familiarity through time spent in a place. This was in part choice but also necessary due to those pesky patent laws in England.

They used personal connections. Hill worked at the Royal Scottish Academy, and his brother had a private gallery nearby on Princes Street. Handy.

They photographed famous people of their day, which helped promote their status and publicised their work.

They worked from home. Their studio was at the house they both shared. Hill was a single father by the time he collaborated with Robert Adamson, and he sadly outlived both his children.

Disasters happened. When Robert Adamson died, Hill lost his business partner, housemate and close friend after only four years of work together. He didn’t channel the pain into artistic success but rather stalled and went back to his former career, painting.

They lost time and money. “I have spent some hundreds of pounds and a huge cantle [part] of my time in these Calotype freaks . . . and if I do not succeed in doing something by it worthy of being mentioned by Artists with honour – I will very likely be soon have done with it,” said Hill.

Art was influenced by what was trendy. New processes appeared quickly, and their calotype method quickly seemed tired in comparison.

Curators made mistakes. In 1975, the Royal Scottish Academy, no less, sold off albums of their calotypes, and the Hill & Adamson collection was broken up and scattered. Some were later acquired by people like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC. Things work out.

Support from their patrons was essential, not only for finance but also for encouragement to keep going with what they were doing.

Just like today . . .

Insights gleaned from Printed Light by John Ward and Sara Stevenson, 1986, Facing the Light by Sara Stevenson, 2002 and A Perfect Chemistry by Anne M. Lyden, 2017.

How about the differences?

When I've been researching Thomas Annan what strikes me is the religiosity of the times, which led to moral decisions overriding financial concerns. The writings of someone like Thomas Carlyle, who was incredibly popular then, seem so incredibly alien from our current outlook.