Artists Shape Landscapes

Can art really drive rural depopulation in Scotland?

The Herald newspaper’s series of the New Highland Clearances reveals the role the artist (whether visual or textual) can play in shaping and marketing landscapes. Dr Rosie Alexander of UWS outlined the challenge to journalist Caroline Wilson:

“There’s a dominant narrative of cities being fast-paced and the centre of industry. Rural is very difficult to define but it’s defined in opposition to urban. If urban is fast paced, centre of industry, the future, rural becomes the opposite and sometimes we can capitalise on this narrative. A lot of ideas about our tourist industry are based on people from cities coming to a slower pace of life, relaxing and engaging with nature. So in some ways a lot of the ways we promote ourselves in tourist literature promote these ideas.”

Art shapes the landscape: both our internal expectations and external shaping to fit that vision. The image of Scotland projected by the tourism boards across the world is one of empty places where you can get away from modern life. This image has been perpetuated by artists feeding a market for romantic idealism. But a land depicted as being only for modern hermits following in the footprints of Celtic saints may deter immigration and innovation.

In fact, the emptiness in Scotland is not a natural vista but cleared land, industrial or post-industrial landscapes which, in great part, are man-made. And the wide open spaces we flee to in order to escape the rat race are themselves global centres of industry: forestry, fishing, food and drink.

Those golden fields are actually the foundation of a trillion-dollar whisky industry. Years back I did a story for the International Herald Tribune about how only 1 in 5 whisky distillers were locally owned. This statistic has not changed.

That hill over there is owned by a French drinks behemoth. This one is the property of an Emirati water company. A trust in Panama runs that glen. Those rings on the bright water are not from otters but are placed by Norwegian multinationals to satisfy sushi makers across Europe and the world. Even the string of cute fishermans' cottages were the enginehouse of an international trade in herrings that once supported hundreds of thousands of people.

You can’t unsee those stories.

I'm not arguing we should evict the foreign multinationals, but I want to show a holistic vision, the reality of a rural industrialised landscape. A place that is open for business. We might struggle to accept this, because we have a certain picture in our mind, one defined in part by artists, poets and writers.

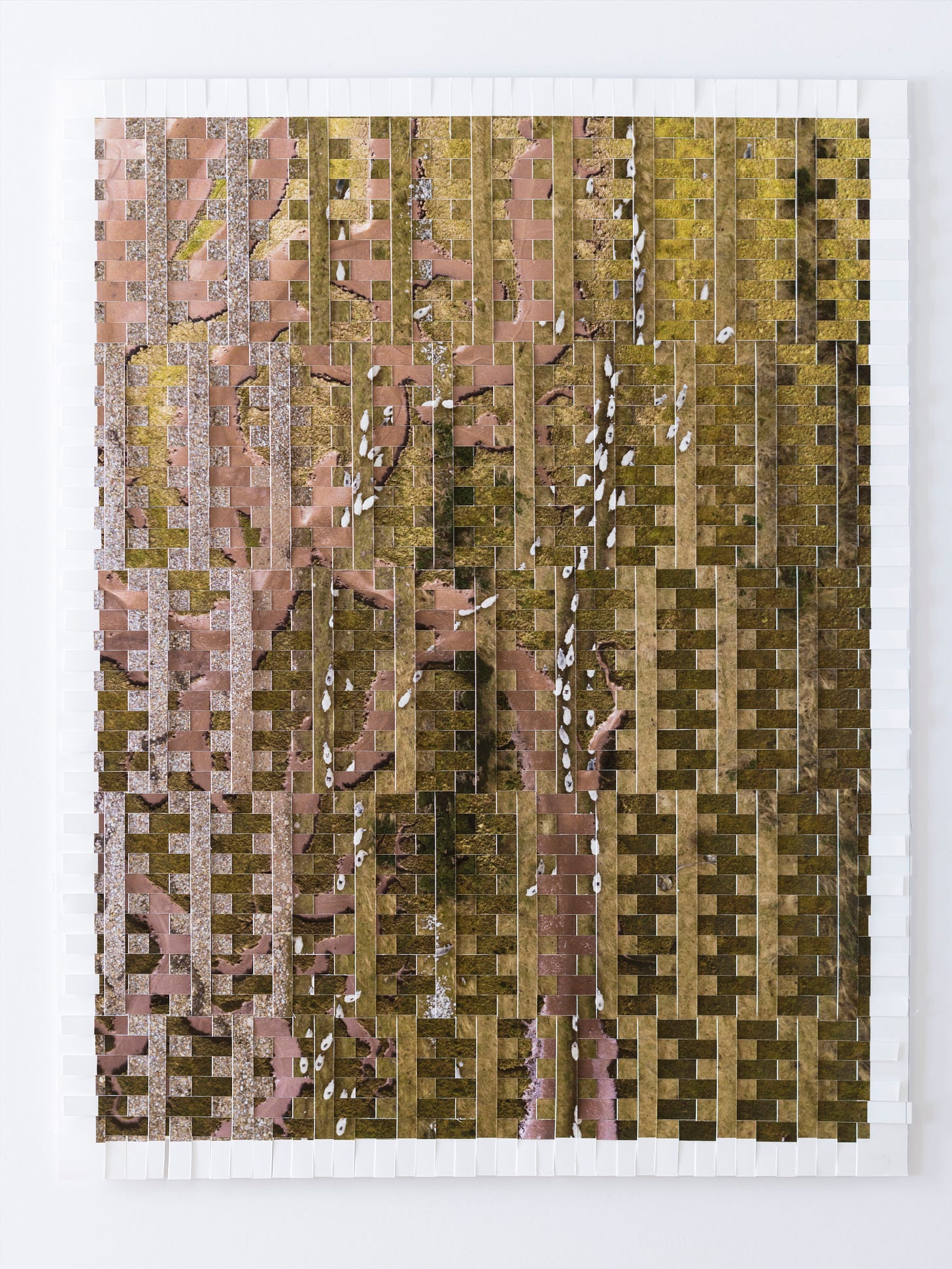

In frustration I have been chopping up my prints as a symbolic restart to telling these complex stories.

Modern Scotland was founded on a mono-economy of textile manufacturing, so weaving these prints together seems apt. I layer industrial narratives onto natural visions, historical views and modern interpretations.

I would love to hear your thoughts about this. Write me a comment below.

Your support of this Substack helps fund the production of new artworks. As well as prints of my weaves, some of the originals are for sale, with more in process.

'The image of Scotland projected by the tourism boards across the world is one of empty places where you can get away from modern life.' ... only to arrive to find that space filled with other tourists who have read the same 'top places to visit' list, unless said tourists are prepared to actually walk a significant distance from their vehicle to find an empty space.

It's incredible how busy the landscape is, however, if you are observant and spot what has been left behind from millennia and centuries ago, and some not so long ago. Many a time I was out on survey, I would stand and listen, imagining the sounds of occupation as I stood amongst barely visible footings of buildings.