On Ginger Extinction and Divine Origins

Myth-busting and map-making

When I saw her across the office she looked really angry, a frown framed by wild golden hair. I approached, and our eyes met briefly, but she was unmoved. As a former magazine cover girl, she now spent her days around the corridors of National Geographic in Washington, D.C. trying to forget the stir she sparked.

Wilma, as you might have suspected, is a model, but not that kind of model: she is an actual model, 200 pounds of silicone, a synthetic incarnation of a Neanderthal woman, created in 2008 for a National Geographic article. She is also strikingly ginger.

On extinction

By the time I met Wilma in person, I had been working on my Gingers series for a couple of years. Many redheads I interviewed claimed jokingly that they were part Neanderthal, or that they were dying out. Was Wilma to blame for this falsehood, I wondered, or was it a wider conspiracy? She refused to comment.

Looking into these ideas, though, I found that Wilma was a mere bystander. The 2008 National Geographic article clearly states that the redhead gene found in Neanderthals is different to that seen in Homo sapiens (they presume ours appeared separately). A 2007 article in the same magazine reassures us that although the gene for ginger hair is recessive and it is possible that the number of gingers will decline, as other press ran with the story in 2007, the potential for redheadness will continue to endure in our DNA. And yet somehow the idea that gingers were Neanderthals and destined for imminent extinction became conflated in the popular imagination with National Geographic and poor Wilma, a model citizen.

Divinely appointed

My Gingers exploration actually began in more recent history: in artworks I had seen in the National Galleries of Scotland. Every painting in the Renaissance room, I noted, had a ginger in it. Usually it was the main subject. Mostly it was Jesus.

I tested this observation in The Hermitage in St Petersburg and most recently in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. this year, and the gingers were everywhere. Those Southern European painters loved to crown Middle Eastern characters with bright golden hair – perhaps as an unmissable sign of divinity? I found it odd that there was very little discussion of this in the art history world. But it struck me that this stereotype of Scottishness held much wider significance, and I soon disappeared down a rabbit hole.

Tracing our ancestors

I love starting research with a map to find my bearings around a topic or a place, perhaps because when I studied ecology at university, we used datasets and formulae to create lots of visuals such as graphs and maps. These could help us untangle complicated ecosystems by representing distributions of different species in an environment.

My first quick Google search of the distribution of ginger hair threw up a tantalisingly dodgy map, without reference to any source material. As you might expect, the Celtic Fringe glows bright, with red spread over Ireland, Scotland and Wales, but what was that hot spot in the east? With more research, I discovered there was a high incidence of redheads in the upper Volga catchment. A Russian chapter for portrait series I was yet to begin already beckoned, to be completed four years later in the city of Perm.

With further digging I found that the ginger gene (MC1R) was discovered in 1995 from a collaboration between academics in Newcastle and Edinburgh that included a dermatologist called Professor Rees. I read through his scientific papers and was interested in one about melanoma (skin cancer) incidence and the MC1R gene in Jamaica! Jamaica did not appear on any dodgy maps, but my trip there, six years later, would become another chapter of my project.

During interviews in each country I visited, participants told me about their ancestral links, which spanned the globe. The country where someone lived was only half the story; for example, in all locations I found gingers with connections to Asia, allowing the series to encircle the earth.

Mapping the New World

My original Gingers book featured portraits of gingers captioned with their name, country and date of birth. When the book was covered on the BBC, I received messages from across the world, including from American gingers, whom I had not photographed up to this point. Some claimed Scots and Irish descent, but there were Native American and Afghan American gingers too. I vowed to visit the States and began in earnest this year.

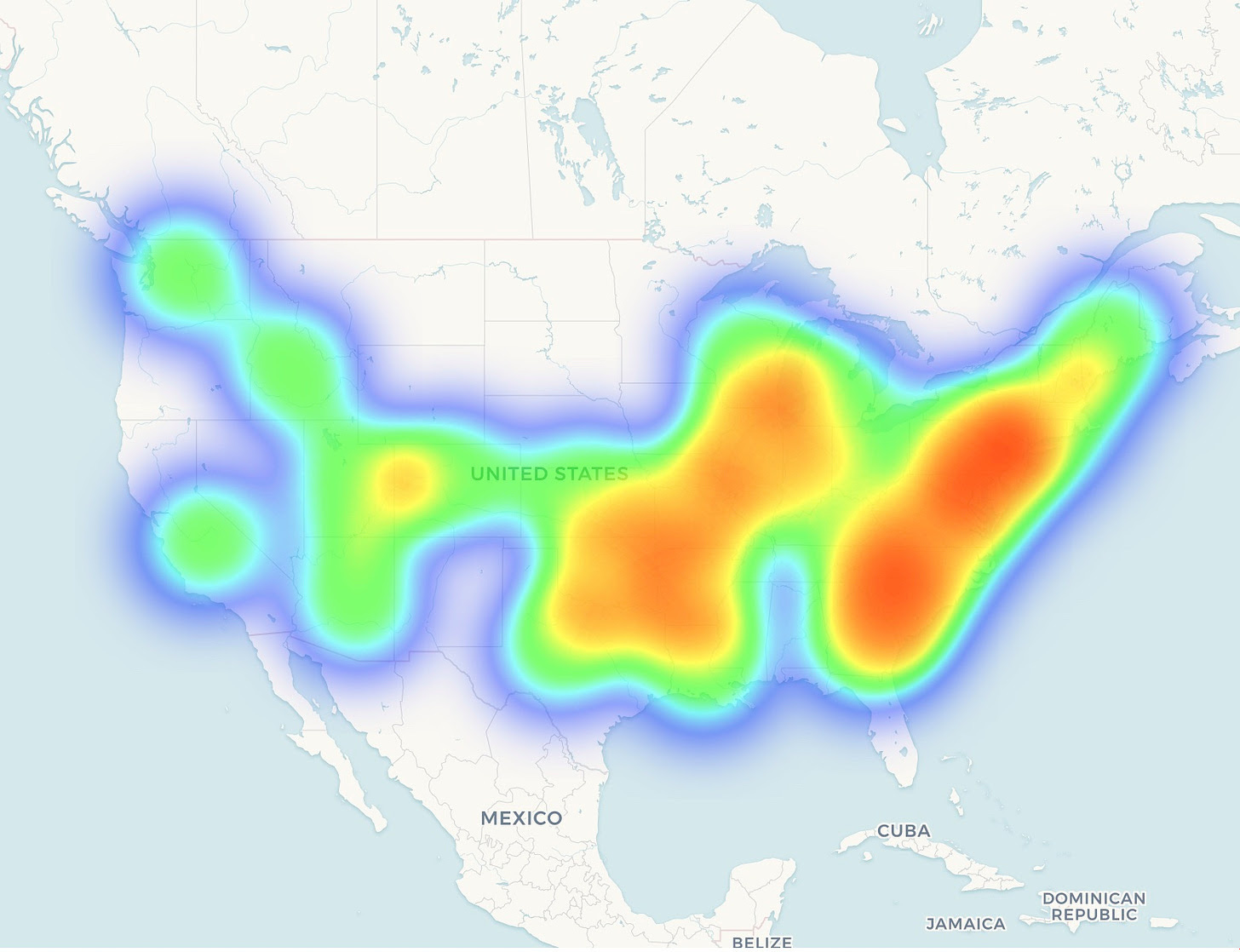

There was, however, little data and a disappointing lack of maps of US ginger distribution, so I have been creating my own dodgy map, using anonymised data from volunteers for the project. Here it is:

Map showing distribution of Gingers of America © Kieran Dodds 2024

There are major flaws in this: a tiny sample size (and exclusively people able to fill in a Google form), the skew towards locations I have visited (so far Arkansa and Oklahoma, D.C., Connecticut, New York and soon Oregon) and the lack of adjustment for population density. Yet, despite my limitations, I have managed to find connections to the majority of the states. People do move around, after all.

Can you help make the data less dodgy?

Where do I head next? How do I get there?

The form is here. Please send it to friends or publicise it online with the hashtag #gingersofamerica. This project is unsponsored and entirely funded by my other projects, including Substack, merchandise, exhibits and teaching in the US.

Next week, I will be correcting more fake news, this time relating to my own process. I have even tracked down the guy who inadvertently made my work into a meme. Watch this space!