Fake Views

Death, Lies and Tartanscapes

It’s Tartan Week in the US, so I have written about a surprising absence of the cloth in the early photographic record. I am also sharing a new photoweave created in response to my reading. And you can read a New York Times story I shot about a 270-year-old fiddle linked to Robert Burns. There is a video of me being interviewed at the end too. Enjoy!

Photographs misrepresent reality, often intentionally. The camera is not wholly innocent, but mostly it is the photographer who lies.

The tragedy of Hippolyte Bayard (1801–1887) is a case in point. He invented photography, but you’ve likely only heard of his contemporary Louis Daguerre, who published first and got the spoils. Poor old Bayard took it hard. Not long after, a photograph of his drowned corpse circulated. Happily it was faked, by Bayard himself, channelling his bitterness into an artistic creation, Self Portrait as a Drowned Man. This began a long tradition of fake views in photography, well before AI.

As an aside: the actual first photo was taken in 1826 or 1827, on the roof of a farmhouse near Le Gras in France, a decade before either Daguerre or Bayard had taken theirs.

The photo below is slightly different – it is an accurate depiction of a false reality, a living fraud whose lies were so persuasive the myth has endured. The audience, including you, may not want to believe the less romantic reality.

The Man, the Myth

In 1829, a letter appeared on the desk of Sir Walter Scott announcing the unique discovery of a manuscript dating back to the 16th century. After being hidden for hundreds of years in a French monastery, then copied by exiled Stuart royalty, the book had survived through skirmish and subterfuge, finding its way to the descendants of the Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie. It held the origin stories of clan tartan, and the book was purportedly hidden for safety during the purging of the cloth by the British.

Scott was the nation’s great historian and novelist, with a love of Highland dress. This had been adopted into military wear in the late 18th century, reversing a ban on the cloth after the Battle of Culloden in 1745. By the start of the 1800s, tartan had become a key motif among heroes and rogues in historical romantic fiction. In 1822, the King wore it on his state visit to Scotland, on Scott’s recommendation, and, by royal assent, it became the official Scottish dress. Scott, more than anyone else, popularised the common Scottish identity we know today.

And for Scott, something in the manuscript jarred. This old text suggested something new, that Highland culture had actually been found across the entire nation, including in the Lowlands, where Scott and most Scots lived, speaking Scots, a language distinct from Gaelic and English. Scott smelled a rat and ignored the book.

Did you know there are also rewards for referring?. Refer two friends to the email and receive a free month of access. Five friends gets three months. Try it today.

Ridiculus Titulus Libro

A decade later, in 1842, the Vestiarium Scoticum appeared in print, presented by two brothers, named Sobieski Stuart, whose father, they claimed, was born in Italy of exiled Stuart royalty. They had decided it was time to reveal this national treasure. The ‘false Latin’ of the title was a sign, to those in the know, as it had been to Scott, that something was wrong. While the sceptical Scott was now dead, Scott mania was alive and sweeping the world, and the book, and the Sobieski Stuart brothers, with their claim to royalty, captured the popular imagination.

Hill and Adamson naturally made portraits of these celebrity brothers, and by documenting things as they were revealed the fraud, even if they didn’t know it fully themselves.

You Will Know Them by Their Cloth

The exhibition Fabric at the Dawn of Photography, currently on show at the National Gallery of Scotland, reveals how the calotype process captured the delicate fibres in textiles. The images also reveal a surprisingly tartan-free Scotland.

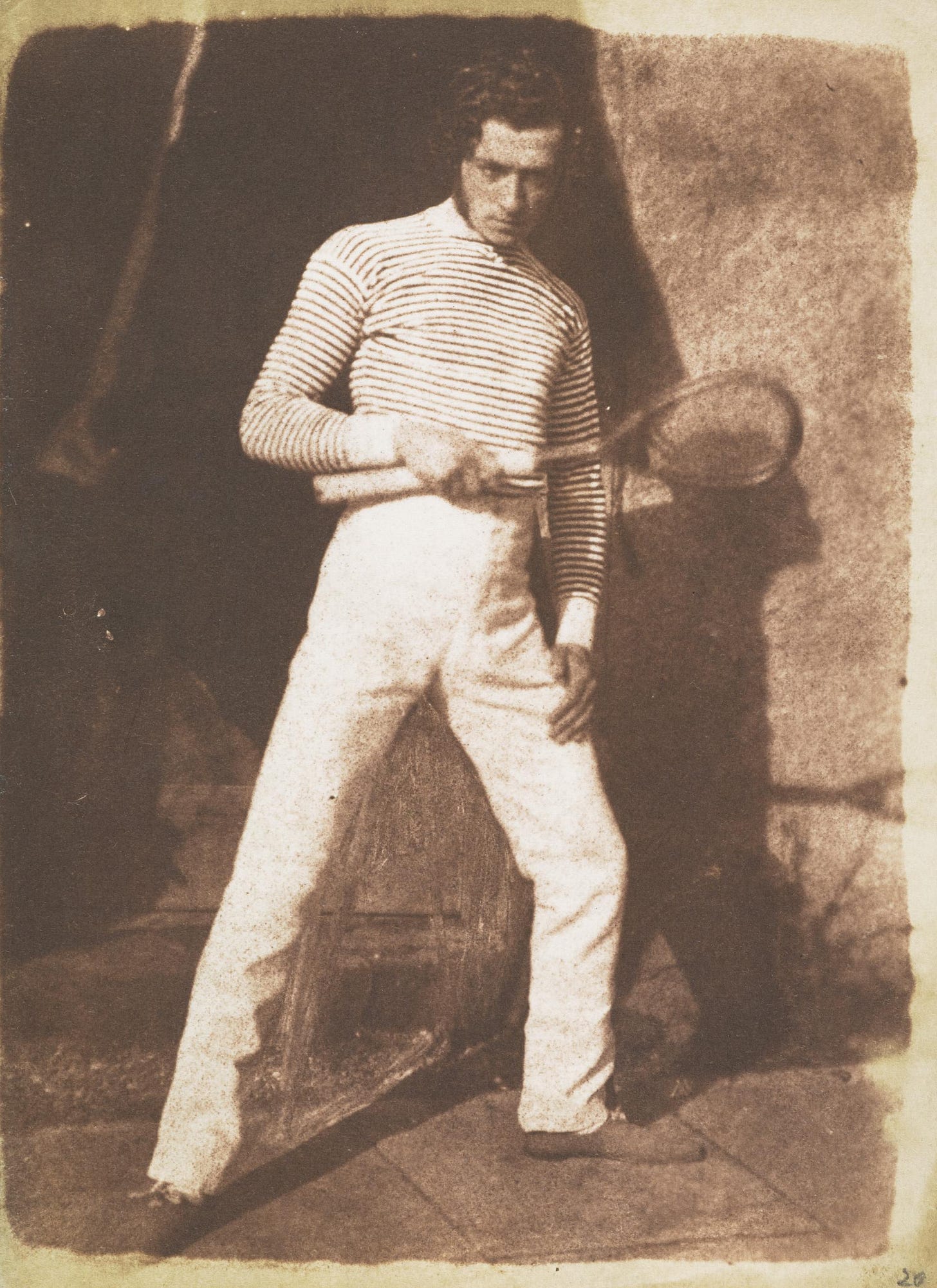

In a few specific portraits, tartan appears on a deer stalker and a professor’s cute child. Elsewhere in Hill & Adamson’s oeuvre it tends only to be worn in ceremony, by the military or by flâneurs like the Sobieski Stuarts. Mostly, the dress is dark and austere, with the occasional striped garb of a sportsman, delicate lace shawls or even exotic oriental wear.

Tartan Fabrications

Today, many still conflate Scottish identity with Highland identity. I recently attended a Scots-themed assembly at my girls’ school here in Edinburgh to coincide with Burns Night. The dress code: tartan. I didn’t mention it on the parents’ WhatsApp group, but Robert Burns (1759–1796), who popularised Scots (not Gaelic) language and culture to the world, rarely, if ever, wore the cloth. Highland dress – including plaids, kilts and tartan – was illegal for Highlanders between 1746 and 1782, most of Burns’ life. Although tartan was not officially banned in the Lowlands, they tended to wear simpler shepherd’s plaids, and any tartan or tweeds were not tied to clan or family. The most famous portrait of Burns was made five years after the ban was lifted, and he appears tartan-free.

I visited the Burns museum for a recent New York Times story, and double-checked his tartanlessness with staff for this article. They agreed broadly. In the entire museum there only seemed to be tartan in the gift shop or on memorabilia made centuries after his life.

Like the early photographs show, although tartan was indeed part of the national fabric of Scotland, it is not the whole story. To miss this is to ignore the richer story that Scotland for centuries was a multicultural and multilingual place, home to Picts, Britons, Gaels, Anglo-Saxons and Norsemen, before it settled into the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and the Scots-speaking Lowlands.

A New Wee Weave

Rock House (Broken Fishbones), 2025

6.5 x 8.5 inches

Archival print, hand-cut and woven

Behind every great Hill & Adamson photograph is … a wall.

This new study weave is created from my photos of the outdoor studio at Rock House in Edinburgh, seen in the setting of Hill & Adamson’s portraits shown above. The orange render at sunset bathes the image in a calotype-esque sepia, while the interrupted herringbone weave is a nod to the duo’s portraits of Newhaven fisherfolk. The resulting image helps me to consider the imposition of the present on the past, and the difficult task of reconstructing fragmented memory.

This last month, I have been sharing and discussing the main ideas around the Fabricated Land series. One day, I hope to create my own fake ancient book with a dodgy Latin title. In the meantime, I am writing this Substack, Now We See. Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Other News

During my time at George Fox University in Oregon, I was interviewed and the video is now online.

The New York Times fiddle story was published at the weekend, perfectly timed for this article about tartan and Scottishness.

Thanks for reading, listening and watching!

Is there an historical novel about Bayard/Daguerre? Off to ask Google…