4. Power

The Poetry of Pits in the Petrochemical Age

A preview of the latest of my new large weaves is included at the end.

Fabricated Land is an ongoing body of work composed of photoweaves of abstract aerial imagery. Each weave tells hidden stories of the past’s influence on the present.

Scottish chemists were busy in the 19th century. When not pioneering the divine solar art of photography, they were patenting techniques to shatter rock in order to extract and distill oil for fuel and lighting. Chemists can yield significant power.

Although the French got there first, as with photography, the Scots refined the petrochemical fractionation process across scores of independent plants in West Lothian near Edinburgh.

Greendykes I, 2021

Archival Photographic print on paper

50 x 37.5 Inches

Edition of 3

Today, the mounds of burned orange waste are a Martian landscape. The metal skeleton of an overturned car resembles a failed Rover mission. Plants struggle to grow on the loose, shattered shale, except for trees and grasses in the lower slack areas. Dirt bikers tear down the slopes, grinning madly at dog walkers. There is life in Broxburn.

These man-made hills are a window into the powerhouse of the industrial past often missing in art.

Technological revolutions often create romantic counter-reactions, as we are finding now in cultural reactions to the surge of AI. Yet when humans flourish, it is often thanks to the interplay of opposing forces. When tourists and artists rushed to the wilds to escape the noise and fumes of the modern world, for example, they did so thanks to the new railways. We fly across the world to experience the world’s great wildernesses. We then post images of these depopulated landscapes. Technology allows us to see the value of the world, to attract others to visit or to champion their protection.

Weaving an Industrial Pattern

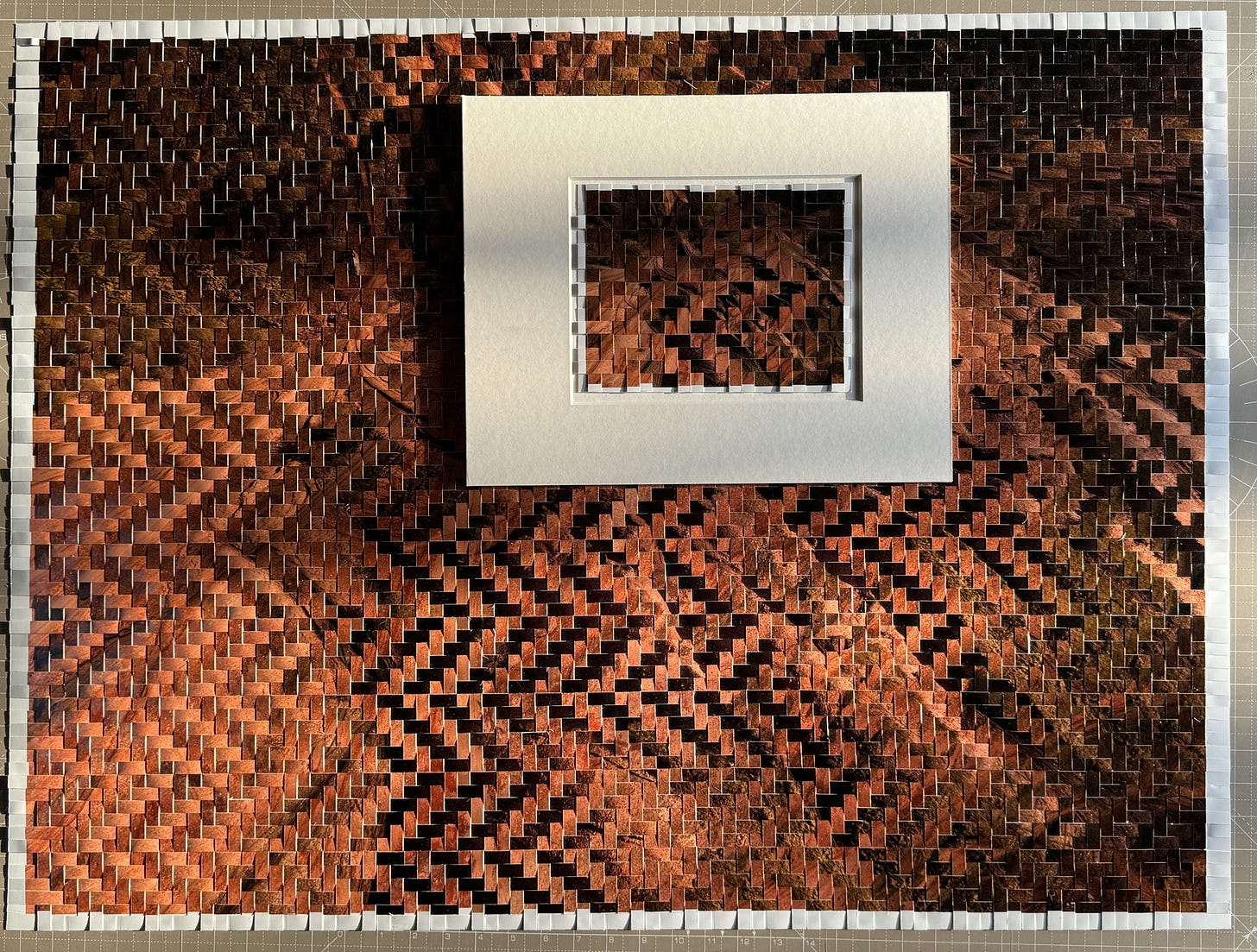

I made a photoweave from the bright reds of Greendykes, in debt to the creative beings who worked in such difficult sites. Those who could imagine the possibilities and experienced the dangers of the new technologies.

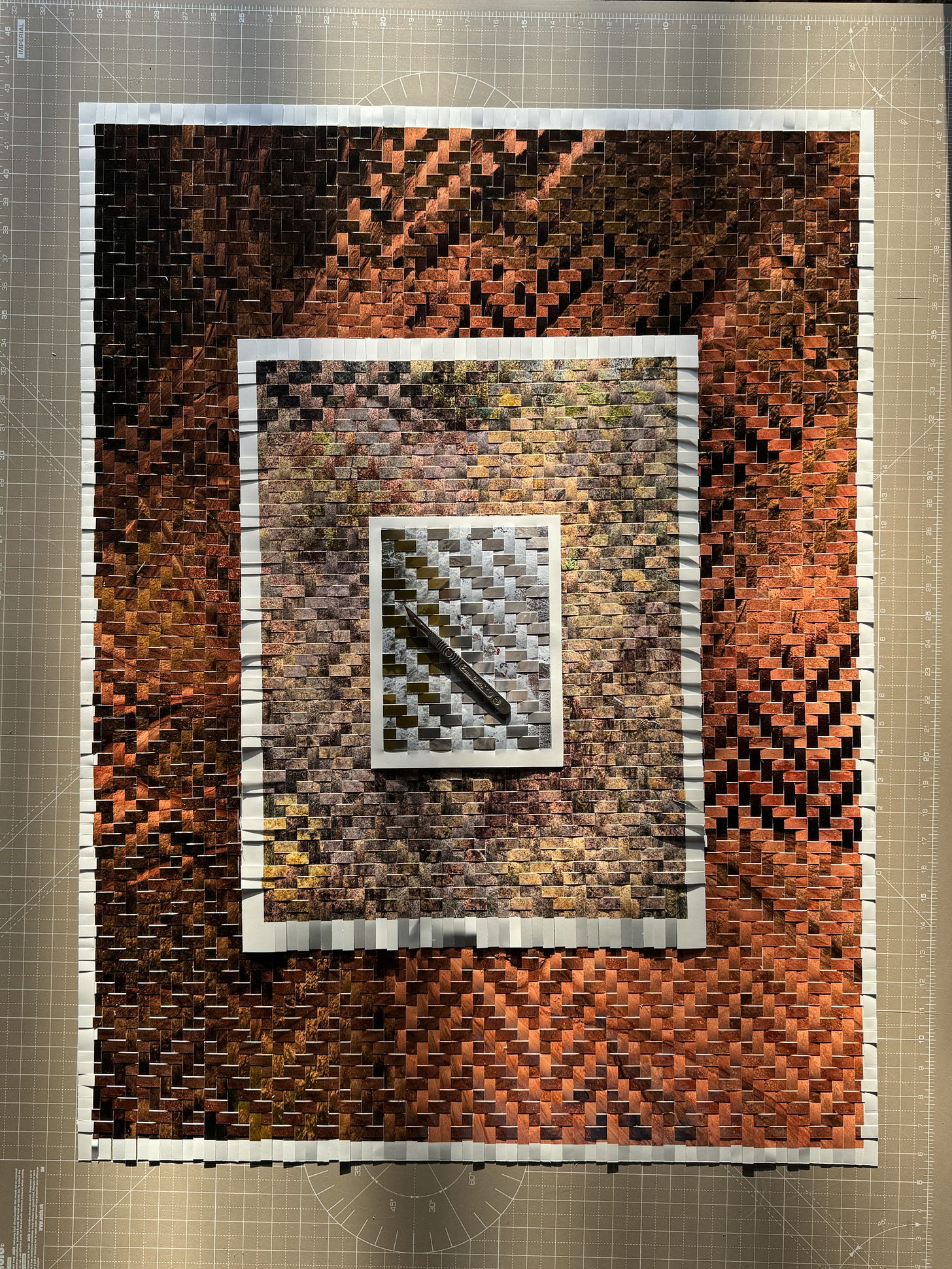

I based this weave on the herringbone pattern. Noting that the shale oil was formed from the bodies of organic life in an ancient ocean, I named my weave Fishbones. Each of my different weave-types uses a specific combination of images and a pattern. This fabrication of culture is a nod to the Sobieski Stuart brothers who invented vast swathes of tartan lore, as I discussed last week.

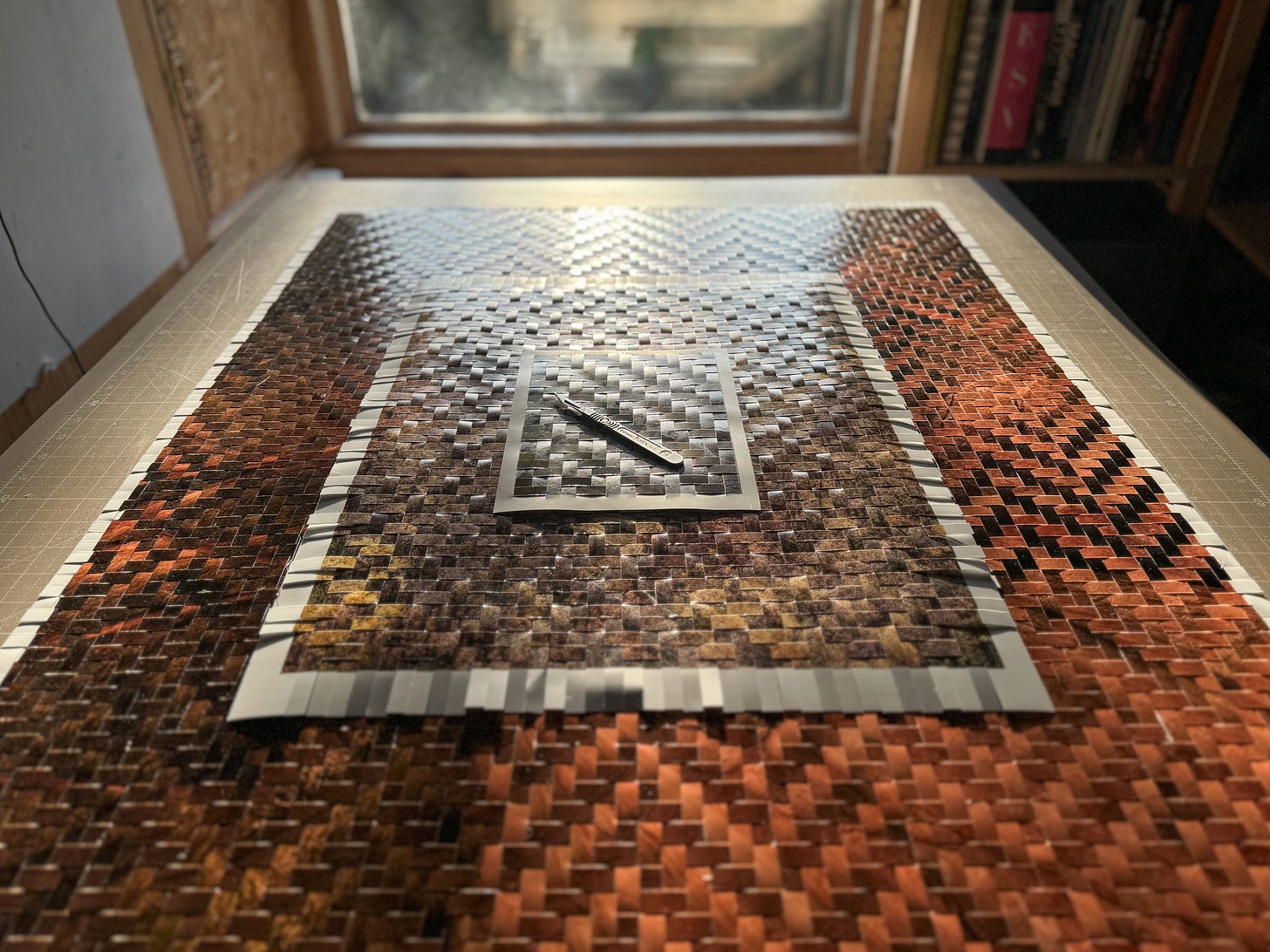

Here is a preview of my largest scale weave in this series, only the second produced at this size, measuring 28.5 x 37.5 inches (72 x 95 cm). I want to create more. I love the play of the pattern and image at different scales.

The three sizes chart the evolution of the technique from small study weaves, where images and weaves are paired, to the largest exhibition print. The medium weave is for part 5 of this series (Romance) and the study weave is for part 6 (Recreate). More on them later.

Collect and Support

Unique, original weaves are available to purchase including the mounted study weave seen above plus this medium one.

Greendykes Bing (Fishbones), 2023

Photographic print on paper, hand-cut and woven

21.5 x 16.5 inches

There are also limited edition archival prints made from unique photographic weaves.

Thanks to those who have supported this email, collected prints and written encouraging messages to keep going. I am having a break next week for the holidays. A Happy Easter to you when it comes!

If you haven’t already come across it I thorough recommend Siobhan Angus’s Camera Geologica which documents photography’s inextricable links to resource exploitation whether it’s animal, vegetable, mineral or human (if that’s not animal too). Climate change, human rights issues, subjugation of indigenous populations and the ruination of lovely places is our (photographers) faults. An over dramatisation perhaps but we aren’t blameless.